Venezuelan Refugees Find a Reluctant Respite in Washington

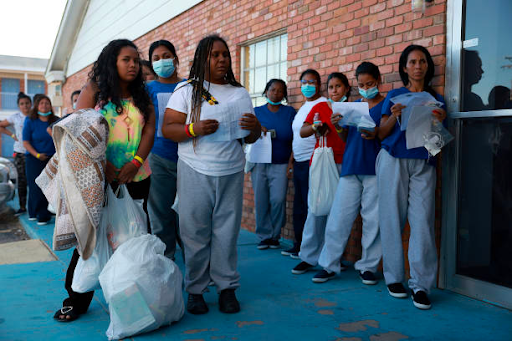

Venezuelan migrants in El Paso waiting to be sent to a city where their sponsor lives. Joe Raedle/Getty Images

By Alexander RodgersCapstone ReportingDecember 14, 20235 MIN READ

WASHINGTON — Amidst the beautiful and evocative landscapes of South America, a dark and heartbreaking reality is unfolding. In particular, the refugee crisis in Venezuela has presented itself as one of the most devastating humanitarian crises of the modern era. The following accounts of Julio and Jose — two migrants impacted by the ongoing crisis in Venezuela — help to illustrate the harrowing tales of survival and chilling accounts of persecution faced by those who have had no other choice but to leave the country.

According to the United Nations, the humanitarian crisis in Venezuela has become the second largest international displacement crisis in the world. An estimated 7.3 million Venezuelans are displaced globally. The causes for fleeing their homeland include violence, inflation, gang-warfare, skyrocketing crime rates, shortages of food, lack of medicine, and lack of essential services. Many millions have been forced to seek refuge in neighboring countries like Colombia and Brazil. According to the same UN Report, an estimated 2,000 people leave Venezuela every day.

However, thousands more have been forced to scatter further afield to the United States. Many have arrived in the United States for reasons that include threats, poverty, and lack of security in other Latin American countries.

And Washington, D.C. is one of those locales.

“I was targeted by a colectivos group for giving away flyers in a pro-government area,” says Julio Garcia, 32, an asylee who fled Venezuela first to Miami and then to Washington, D.C. in 2016. Armed paramilitary groups, known as colectivos, are far-left Venezuelan armed gangs that support Nicolás Maduro and the ruling party. Colectivos usually operate in poverty-stricken areas and attack individuals by engaging in extortion, kidnapping, and drug trafficking. According to Human Rights Watch, they commit extrajudicial killings and even engage in terrorism against those who are against the current regime. “They do the government's wishes,” he continues.

Julio Garcia, above, fled his homeland in Venezuela to the United States as a political asylum seeker. Alexander Rodgers — George Washington University

“They came to us and threatened us with weapons,” Garcia says. “I didn’t want any trouble.”

But despite the trauma of being forced to flee from home, Julio has managed to establish a business as a personal instructor in the Shaw neighborhood of Washington, D.C. And, ultimately, he managed to obtain protected status in the United States as an asylee.

According to a United Nations report, Venezuela has one of the highest rates in Latin America of killings by state agents.

José, pictured above above, left Venezuela with his family through the treacherous Darién Gap. Alexander Rodgers — George Washington University

‘It was eight days walking in the jungle without food’

“The first major challenge was the jungle — el Darién, because it was eight days walking in the jungle without food,” says José who, along with his family, was forced to flee from Venezuela. “There were many people in need. Even when we carried a bag with food, people took it from us.”

“We had to leave because my cousin was killed, and we couldn't stay because we were in the same danger. Even when he and his family left, they burned down his house” continues José. “We had not decided to come to the US at first. It was on the way that we decided to come to the U.S. Initially, we left for Costa Rica, we were looking for anywhere that was better.”

José, like many Venezuelan refugees fleeing their homeland, are forced to flee through the treacherous Darién Gap — a rugged, undeveloped stretch of jungle along the border of Colombia and Panama that many migrants trek through in their journey to the United States. It is the major migrant line between South and Central America.

“It was very hard, it was seeing dead people; walking a lot; not having food; and going through mud, rivers, and rocks,” continues José who now works as a rideshare driver in Washington, D.C. “The children had a very hard time and suffered a lot too. We had to leave [Venezuela] because my cousin was killed, and we couldn't stay because we were in the same danger.”

“The second most difficult part was Mexico. The immigration [into] Mexico was crazy, they kept catching us,” José continues. When we continued walking, the immigration would send us back again.”

Although José and his family now continue their lives in Washington, D.C., their struggle to adapt to a new life continues. José and his family now live in a hotel with other Venezuelan migrants located on New York Avenue. But he is not alone — many other refugees from Venezuela have sought refuge in the Washington region.

According to an article by Washington D.C. CBS affiliate network WUSA9, the District Department of Human Services has tracked 149 migrant buses arriving in the region since October of 2022 — when the Office of Migrant Services was established by Mayor Muriel Bowser. Furthermore, the article states that the D.C. government has provided temporary lodging for over 1,500 migrants according to a DHS spokesperson.

The Ethiopian Community Development Council — an aid organization helping to resettle refugees from around the world in the Washington region — states that “resettlement is not only a humanitarian act to save lives and offer safety and protection to the most vulnerable individuals, which is in line with the values America was founded upon.” The organization continues, “There are many cities in the U.S. that have an aging and declining population and are actively looking to increase their working-age population. Welcoming refugees is one strategy to accomplish this goal.”

“It’s a specific period in their lives that [refugees and asylees] are having these problems,” says Esra Bayraktar, an immigration lawyer and case manager at the Ethiopian Community Development Council. “In a few years they will be adjusted to the society — to life in the United States.”

Stories like Julio’s and José’s illustrate the struggles of those who are forced to flee and help to give a glimpse into one of the most important migration crises of the modern era.

To help explain why he left, Julio likens his experience to the tale of the boiling frog — a popular myth which suggests that if you put a frog in a pot of boiling water it will instantly leap out. However, if you place it in a pot with mild water and gradually warm it, the frog will remain in the water until it is eventually boiled to death.

“It gradually reached a point where I could no longer stay — the food rations, the violence,” says Julio. “I had to leave.”

Both Julio and José embody the resolve and determination of countless Venezuelan refugees who, despite all odds, have started on a journey to a better and safer future in the United States. Despite the hardships faced, their collective strength has created a tapestry of stories that intertwine with determination and perseverance. The difficult choice to leave behind a homeland has etched everlasting scars on the hearts of those who, like them, bear the burden of abandoning a previous life.

This struggle for survival persists in the stories of those who have been forced to flee. And while Julio and José’s journey to safety may signify the end of one chapter, the uncertainty that looms ahead casts an ominous shadow over the shared fate of countless others.